(RNS) — For the purposes of marketing and political polling, it has become fashionable in recent decades to demarcate and name generations of the nation’s citizens — Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials (also Gen Ys) and Gen Z. Even if these generational boxes seem cramped and sometimes create false divisions, we owe a lot to social scientists for the insight they have brought to our common national life with these generational groupings.

What is more, the generational demarcations that have proven useful for marketing and polling purposes also enable us to catch sight not only of similarities among these particular age groups, but also the rough outlines of trends important for our civic life.

Now and then, they even give us sightings of religion, and, correlatively, non-religious trends with helpful designations, say, in addition to Baby Boomers (etc.), the “Nones,” that is, the growing demographic of people with no formal religious affiliation. As the United Methodists are being torn apart, as the clergy crisis continues among Catholics, the Nones keep adding numbers so that they are about one-quarter of the population.

It is to this situation that Nicholas Kristof, a well-known columnist for The New York Times, recently wrote a fine opinion piece, “We’re Less and Less a Christian Nation, and I Blame Some Blowhards.” His point was one that has, in part, been made by many observers of the American scene, namely that millennials are leaving the churches and not returning. Kristof relies on a Pew Research Center study that found that only 49% of millennials think of themselves as Christian as opposed to 84% of Americans in their seventies and older.

Of course, our nation is, happily, becoming more diverse racially, religiously, ethnically and linguistically. And generational and life-cycle issues are very much in play here, as others have noted: millennials are busy working, advancing careers, starting and having families, in some cases are in their second marriages, and, given those realities, are often opting out of membership in religious institutions, ostensibly (hopefully) to return later. But they’re not returning.

Why not? That is the question.

Kristof’s conclusion, which this author thinks is at least part of the explanation, is that the “central issue is that faith is to provide moral guidance — and many moralizing figures on the evangelical right don’t impress young people as moral at all.” As he notes, LGBTQ folks have significantly greater approval among millennials than evangelicals. So, the nub of the problem is, not surprisingly, the age-old question of the relation of faith and morality, religion and ethics.

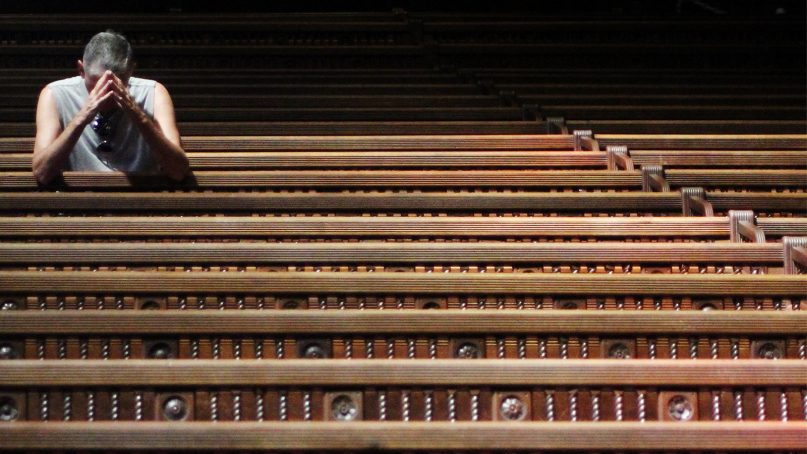

Photo by Andreas160578 from Pixabay/Creative Commons

While Dostoevsky worried that without God everything is possible, it seems now, for millennials at least, that with God everything should be expected. And while religion in the U.S. has always been of a rather moralist stripe, owing not only to those strict Puritans but to others as well, that seems to be shifting under our feet, for good or ill.

Even Tocqueville thought that American mores carried by the nation’s women and its Catholic and Protestant religion traveled together in the creation of democracy on these shores. His worry, I suppose, would be about the viability of democracy when its religious and moral resources run dry, whether those resources are Christian or not.

So, this moment, granting the sociologist’s data, it is perhaps more complicated than it might first appear. Are we witnessing a reversal or seismic shift in the nation’s religiosity, at least its Christian form?

Recall that the nation has undergone several “Great Awakenings” in the past centuries. While historians debate whether there have been two, three or four “awakenings” (or if we should describe them as “awakenings” at all!) between the 18th and 20th centuries, in each case there was an upswing of interest in religion, a focus on sin and redemption, and an increase in religious identification, especially among evangelical Christians.

Just as importantly, it should be noted that each “awakening” was, in distinctive ways, a moral movement as well against perceived social and private sins. For example, what Jon Butler has described as the “antebellum spiritual hothouse” — late 18th until the middle of the 19th century — teemed with reform movements around temperance, women’s rights and abolition. The so-called “Third Awakening” gave rise to the renowned “Social Gospel” and its concern for workers’ rights, just wages and the like, against the abuses of crass and craven industrial capitalism.

Regardless of how you think about these movements in American Christianity or how you divvy them up, the important point for our purposes is that despite their seemingly conservative religious bent — steeped in rhetoric of sin and redemption — there was, with notable exceptions, often enough a progressive moral, social and political agenda for its time.

How odd, then, that the current custodians of the evangelical movements would be seen, rightly this author judges, as anything but progressive and in fact stunting the work of churches to labor for greater freedom, inclusion, aid and equality of people as marks of a robust religiousness. Maybe the millennials are seeing what too many Christians are not.

Is it possible that we are living through “The Great American Slumber,” a time when too many churches are not pressing for the reform of the nation but lining their pockets, becoming court evangelicals and traveling around by private jets? Are these churches asleep while the youth of the nation are “woke?”

If that is the case, one can only hope, as this author does, that the number of awakened millennials grows and that they evangelize the slumbering churches.

(William Schweiker is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago. This article originally appeared in Sightings, a publication of the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)